Remember How He Lived

It is hard to fathom today, but 25 years ago, the world seemed a much simpler place. Long before global terrorism was a part of our daily dialogue and in a day when the World Trade Center towers still stood in the heart of New York City, our nation suffered an unimaginable tragedy.

Shortly after 9 a.m. on April 19, 1995, a truck with a bomb made out of fertilizer exploded just outside the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in downtown Oklahoma City. The bomb ripped off one side of the building and caused mass destruction. Later determined to be a domestic terrorist attack by a man infuriated with the U.S. government, the cowardly terroristic act took the lives of 168 individuals, including children in a daycare housed in the building.

Like many who were old enough to remember that day, I recall where I was when I first heard the news. It was just days after Arkansas had advanced to its second consecutive NCAA Men’s Basketball Tournament National Championship Game, falling just shy of back-to-back national titles under legendary Coach Nolan Richardson.

I was at work at the Southeastern Conference in Birmingham, Alabama, where I was an intern in the media relations department. I remember heading to the break room to watch the horrific images flash across the TV screen.

Television has an amazing ability to bring us closer to events around the world. Yet, in a strange way, it also can desensitize us to the realities of what is portrayed. After all, with television, we still have the option to turn the channel or simply turn off the images – almost as a coping mechanism of removing ourselves from the disturbing events.

I had relatives in Oklahoma City, but none that I believed worked in the building or would have reason to be there. Fortunately, they were not. They were safe. Yet in the hours and days to come, a loss in the Razorback Family would bring that tragedy home in a way not first anticipated.

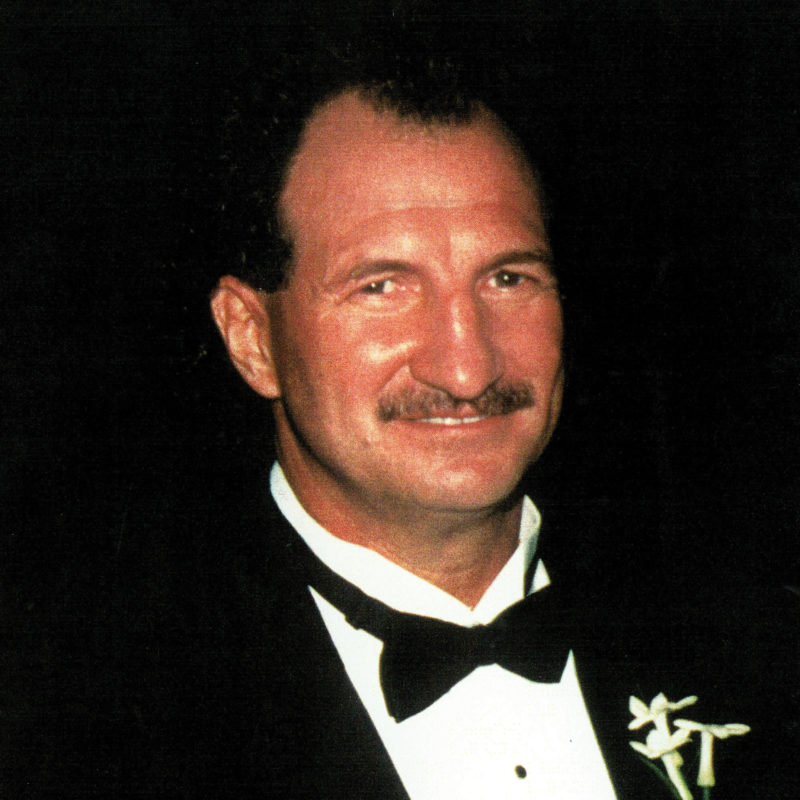

Mickey Maroney arrived at the University of Arkansas during what remains the golden era of Razorback Football. The Wichita Falls, Texas native had already experienced success on the football field. In 1961 as a high school junior, Maroney helped lead his high school to a Texas state championship. His abilities caught the eyes of Arkansas coaches and after graduating from Wichita Falls High School in 1963, he packed his bags for Fayetteville with a scholarship in tow.

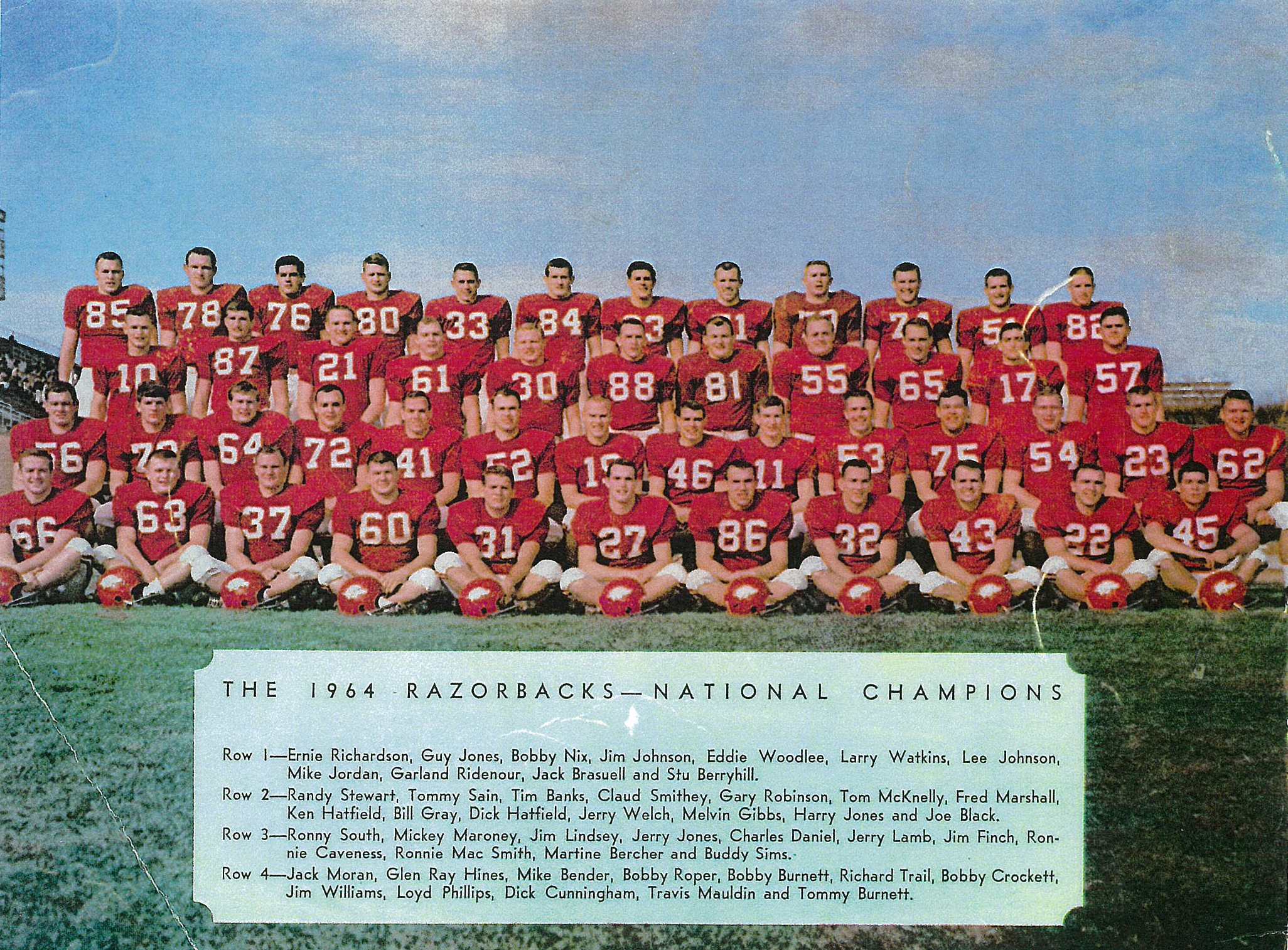

After sitting out his freshman year, as required by NCAA rules in those days, Maroney earned a spot as a reserve on the Razorback defense in 1964. The 6-3, 200 pound defensive end was part of one of the most formidable defensive units in the history of college football. Arkansas recorded five-consecutive shutouts to end the regular season before topping Nebraska in the 1965 Cotton Bowl to secure a perfect 11-0 season and a national championship.

In his junior and senior seasons, Maroney was part of Razorback teams that went 10-1 and 8-2, respectively. By the time his collegiate playing days came to an end, Maroney had contributed to a three-year team record of 29-3 and a bevy of accomplishments, including two Southwest Conference championships, two top-10 national finishes and the school’s only football national championship. The epic run helped put Arkansas on the map in college football as one of the most dominant programs in the nation in the 1960s.

After a decorated college career on and off the field, Maroney was recruited once again – this time for another team of national consequence. In 1971, the United States Secret Service invited Maroney to join its ranks.

Over the next 24 years, Maroney would shine in his duty to his country including serving on the protective details of several U.S. Presidents and other national figures. Maroney escorted Senator Edward Kennedy on the Democrat’s bid for the Presidency in 1980. He also served two years on the protective detail for First Lady, Lady Bird Johnson.

Even while his career blossomed and new opportunities presented themselves, Maroney stayed true to what he treasured most. In a 2015 article in the Los Angeles Times, a colleague Jack Kippenburger noted that Maroney turned down many promotions to stay close to his children and to remain in the Oklahoma-Texas area. He was a staple in his community and a leader in his church congregation at Council Road Baptist Church in Oklahoma City. He taught Sunday School and was a mentor to college men, many of whom went on to serve in ministry. The fellowship hall at the church now bears his name.

Maroney stayed close to his Razorback roots as well. He was active in the A Club, an organization for former Razorback student-athletes and returned for reunions to visit former teammates. Things are never perfect, but Maroney’s life was content.

On the morning of April 15, 1995, Maroney reported to his office on the ninth floor of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in downtown Oklahoma City. Maroney, 50, had served in the U.S. Secret Service nearly half his life. It was more than a job – it was his calling.

At 9:02 a.m., an explosion rocked the Murrah Building and changed things forever. The blast and its ripple effects killed 168 innocent people, including children and eight federal agents, including Mickey Maroney.

When news of the blast reached them, Maroney’s daughter Alice Ann Denison and his son Mickey Maroney Jr. rushed toward downtown. Perimeter barricades set up by law enforcement would not allow them to get closer than just a few blocks. They checked the hospitals for their father and privately hoped he was still inside helping others to safety, as he had done so many times before.

A few days later, one of Maroney’s friends, a firefighter positively identified his body as one of the victims of this horrific act. Just a month before, Maroney had walked his daughter Alice Ann (Maroney) Denison down the aisle at her wedding. Now, suddenly, her father was gone.

In an article in the Duncan (Okla.) Banner in 2015, Denison spoke of the difficulties of the days, months and years following the tragedy. Although, gripped by grief, Alice Ann forged ahead just like her father would have wanted her to do. She testified in the trial of Terry Nichols, one of the conspirators of the bombing and attended the trial of Timothy McVeigh, the convicted bomber. She also worked with the Habeas Group, to help pass the Anti-terrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act (AEDPA), which shortened the time between death sentences and executions.

In 2014, the University of Arkansas welcomed back members of its 1964 Razorback Football team on the 50th anniversary of its national championship. Alice Ann Denison and Mickey Maroney Jr. made certain they were in attendance.

As teammates gathered to tell old stories and reminisce about days gone by, it also provided a golden opportunity for many to share with Maroney’s family the impact he made in their lives. At a banquet, Alice Ann and Mickey were presented with a 1964 commemorative championship ring by Coach Frank Broyles and Director of Athletics Jeff Long. The next day, Mickey joined his father’s teammates on the field at Donald W. Reynolds Razorback Stadium as the 1964 team was recognized.

I thought back to that special weekend recently as the 25th anniversary of the Oklahoma City bombing was commemorated. Due to the current pandemic, a large scale celebration in Oklahoma City had to be altered into an online celebration, highlighted by an hour-long tribute video. Bob Denison, Alice Ann’s husband and Maroney’s son-in-law, participated in one of the most touching parts of the video tribute. The names of all 168 victims were read one by one. Bob Denison read the names of those lost from the U.S. Secret Service, including his father-in-law.

A quarter-century later, the pain is still real. The loss is still felt. Yet the memories of those gone are still remembered. In the case of Mickey Maroney, his legacy remains alive through his loved ones, his friends and those in the Razorback Family.

Perhaps Maroney’s daughter, Alice Ann Denison, put it best in that 2015 article on the 20th anniversary of the bombing. “One of the biggest compliments I can receive is ‘you’re your father’s daughter. He was an amazing father; he was a hero, not because of how he died, but how he lived.”

Razorback Road is a column written by Senior Associate Athletic Director for Public Relations and Former Student-Athlete Engagement Kevin Trainor (@KTHogs). Trainor is a graduate of the University of Arkansas and has worked for Razorback Athletics for more than 25 years.

"He was a hero, not because of how he died, but how he lived.” - Alice Ann Denison (Mickey Maroney's daughter)