A Glance Inside the Door

Like many of you, I have spent much of the past few weeks watching and listening. The inexplicable murder of George Floyd has shaken our nation to the core as we continue to come to grips with the unheard voices and who we are, who we thought we were and who we want to be.

This is certainly not the first time a black man has been killed by members of law enforcement. It is a storyline that has played out far too many times, even in just the past few weeks. However, the combination of a series of incidents involving the murder of black men and women, the power of a cell phone video and a brewing lifetime of anger and frustration over continued social injustice for men and women of color, has all contributed to a seismic societal event not fully felt since the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center of September 11, 2001.

Unity prevailed in the days and months following 9/11 as we bound together to fight the evils of terrorists perpetrated by aggressors hidden thousands of miles from home. Yet this time our nation is struggling to find strands of unity, but the multi-racial protests inspire some measure of hope for the future. The strongholds of racism and social injustice reside within our own borders and in some hearts. The divide seems wider than ever.

This earthquake for equality did not arrive without warning. Yet, not all of us heeded the shockwaves. For many white Americans, the events of the past few weeks have served as an unmistakable wake up call, or at minimum, raised the consciousness of so many. The business of our daily life often masked the racial tremors that have caused damage for generations. Now, there is no mistaking the chasm.

Many want to help, but do not know how. Paralyzed by the fear of uttering errant words or sentiments, we often find it safer to stay silent. Yet the silence compounds the hurt even more. For many, silence is indifference. And as holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel said, “The opposite of love is not hate, it’s indifference.”

Answers will not come easily. Even accompanied with the purest of motives, attempting to find quick-fix solutions to this age-old scourge on society would be like trying to perform open-heart surgery before you have opened a medical book, much less graduated from medical school. For those of us new to the fight, before we act boldly, we must listen and learn humbly. As Americans, we have a civic responsibility to learn from the past and present to ensure the promises of the U.S. Constitution apply to all citizens.

When it comes to the matters of race, sports have often been a spark for change. The enduring courage of Jackie Robinson, Jack Johnson, Jesse Owens and others helped to break down barriers and pave the way for people of color in sports and beyond. Closer to home here in Arkansas, men like Darrell Brown, Jon Richardson, Thomas Johnson, Vernon Murphy, Almer Lee and The Triplets all did their part to chip away at long-held prejudices. Slowly, rosters began to diversify.

By the time I arrived at the University of Arkansas in 1990, the Razorbacks were already Rollin’ with Nolan. Coach Nolan Richardson had just led the Hogs to the Final Four, in what was the dawn of the most prolific decade of basketball in Arkansas history. Over the next four years as a student assistant in the sports information department, I had a front row seat to watch Coach Richardson guide his teams to historic wins and unprecedented heights.

The pinnacle of that magical ride came during my senior year in 1993-94 when Razorback Basketball found itself squarely in the spotlight at the middle of the college basketball universe. By the time Arkansas dispatched of Arizona in Saturday’s national semifinal at the 1994 Final Four, the entire state was anxious for a coronation. An Arkansas win over Duke in the National Championship Game on Monday night, would not only put a stamp of acceptance on the Razorback program and the state, but also serve as a lasting endorsement for its black head coach – Nolan Richardson.

As Sunday dawned in Charlotte, the pundits were already breaking down the penultimate game. On one bench, you had an experienced laden Duke team led by Mike Krzyzewski, a two-time national championship coach whose basketball artistry was admired with the same reverence of Michelangelo. On the other, a high-flying, free-wheeling athletic Arkansas team led by Nolan Richardson, the original architect of a fast-paced style of basketball coined “40 Minutes of Hell.”

In an appearance on ESPN’s Sports Reporters, Mitch Albom, of the Detroit Free Press, diluted his game prediction down to one factor. “The smarter team will win,” Albom said before picking Duke to win the title game. On the surface, Albom’s argument seemed plausible. Duke had won national titles in 1991 and 1992 and had the championship pedigree that Arkansas was seeking. To me, a white 22-year-old male, the words were disturbing only in a way that alienated my passionate bias for the Hogs and my general disdain for the Blue Devils.

However, later that day as I sat in the Championship Game press conference, I began to understand how Albom’s words, even while seemingly offered as basketball analysis, cut much deeper for those with differing life experiences. Filtered through the prism of color, the words struck chords of deeper seeded stereotypes that black players were simply great athletes, while white players were smarter. Coach Richardson used the national forum of his press conference to challenge those words and address the lack of respect for his team and other black coaches around the nation.

It was far from the feel good script of a coach preparing to compete for a national championship. It left many, a bit perplexed, not necessarily for the message, but the timing of delivery on the eve of what could very well be Arkansas’ One Shining Moment.

Back at the hotel that evening, I was asked to deliver some updated Duke statistics and box scores to Coach Richardson’s hotel room for some last-minute game planning. As I knocked on the door, I could hear a cascade of voices and a flurry of activity. The door flung open and Coach Richardson stood in the door frame. I handed him the materials and asked him if he needed anything else. He politely answered no and thanked me for stopping by.

But as the door remained ajar for just a few additional seconds, I glanced past Coach Richardson and into his suite where I saw several men I clearly recognized. It was a gathering of some of the most prominent college basketball coaches in the nation, including Georgetown’s John Thompson, Temple’s John Chaney, USC’s George Raveling and Tulsa’s Tubby Smith.

It was at that moment that I began to understand that what Coach Richardson would be shouldering on Monday night was more than just the hopes of Razorback fans. This was an opportunity to provide a watershed moment for black coaches still fighting for respect and recognition in the coaching fraternity. With an Arkansas win, Coach Richardson would become only the second black men’s basketball coach (Thompson) to win a national championship. It is unlikely that Coach K felt a similar burden of responsibility to win a title to aid the advancement of other white men’s basketball coaches.

The next evening at the Charlotte Coliseum, Coach Richardson led the Razorbacks to a 76-72 win to clinch the 1994 NCAA Men’s Basketball Championship. Richardson became the first coach ever to win a national junior college, NIT and NCAA Championship, an accomplishment that still accentuates his Hall of Fame career.

I was reminded of my brief glimpse inside that Charlotte hotel room door this past week as I listened to numerous black friends and colleagues share a view of the world through the lens of their own life experiences. I am grateful for their courage and their candor. Their words were powerful and educational to someone who can never fully understand life from that perspective. I was reminded of the deep connection felt between men and women of color, even if they have never met. They are linked by all-too familiar challenges and shared hope for a common goal.

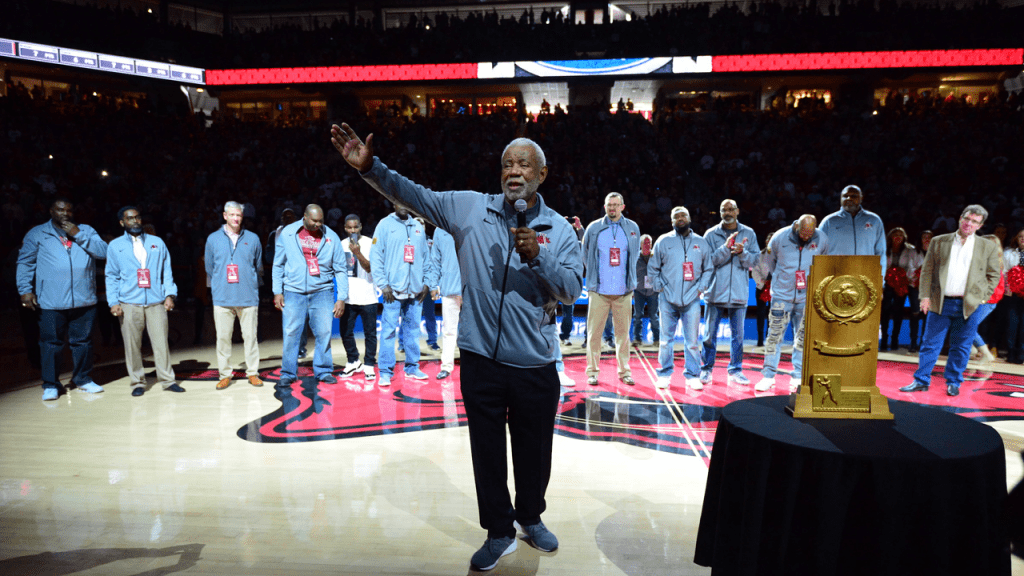

In a fairy tale, the pages detailing the magical 1994 NCAA Championship would have undoubtedly concluded with the phrase “and they all lived happily ever after.” But life is more complicated than that. The years to come would be filled with a roller coaster of emotions. More wins, more losses, a dismissal, a lawsuit, powerful words and feelings, time, gradual reconciliation, a reunion and the dedication and unveiling of Coach Nolan Richardson Court at Bud Walton Arena all were part of the story.

The path to resolution is never easy. We have miles upon miles to go. But as Coach Richardson often says, “A rickety ride is better than a smooth walk.” Time for us all to get aboard.

Razorback Road is a column written by Senior Associate Athletic Director for Public Relations and Former Student-Athlete Engagement Kevin Trainor (@KTHogs). Trainor is a graduate of the University of Arkansas and has worked for Razorback Athletics for more than 25 years.